Today marks 1380 years since of the death of Isidore of Seville (c.560-636), the famous sixth-/seventh-century Spanish archbishop and scholar. As a diverse writer, who synthesized ideas from the late antique world (including both pagan and Christian authors), his works were significant, influential, and highly popular touchstones for medieval thinkers. This British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog post highlights some of his work. For the Roman Catholic Church, Pope Clement VIII canonized him in 1598, and he was declared a Doctor of the Church in 1722. In the twenty-first century, people might know Isidore as the patron saint of the internet–along with computer users, computer technicians, programmers, and students.

Isidore, his works, and their afterlife represent a fusion of several things that I love: a bridge between cultures (late antique and medieval periods), encyclopedic knowledge, and the possibilities of information transmission across the longue durée of media history. As a general characteristic of his scholarship, Isidore set out to capture, synthesize, organize, and preserve the knowledge of his predecessors for future thinkers. These impulses are particularly pronounced in his most famous work, the Etymologies–a striking case for considering how Isidore’s work represents old media practices in premodern manuscript culture.

Above (clockwise): Excerpts from Isidore’s Etymologies, Book VII, in St. Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 230 (c.800), p. 93; beginning of Isidore’s Etymologies in Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 92 (13th c.), fol. 1r; and detail of “De caelo” from Isidore’s De natura rerum in Zofingen, Stadtbibliothek, Pa 32 (9th c.), fol. 62r. All images in this post are from e-codices: Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland, used under a Creative Commons License.

In the Etymologies, Isidore aims to collect and transmit knowledge in something like a comprehensive encyclopedia, covering topics ranging from classical liberal arts like grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, medicine, laws, science, and music, as well as notes on the Bible, God, angels, saints, languages, peoples, geographies, animals, elements, earthly and heavenly topography, urban and rural spaces, natural resources, agriculture, military, maritime navigation, and domestic subjects. While Isidore never completed his massive work, it nonetheless contains 20 books with a total of 448 chapters, relying on around 475 texts from over 200 authors. (For an excellent overview of Isidore’s life and his Etymologies, see the “Introduction” in The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghoff, with the collaboration of Muriel Hall (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006), 3-28.)

Considering Isidore’s task and accomplishment with the Etymologies, it is no surprise that he has been deemed the patron saint of the internet. Thinking in terms of our own information-overloaded digital age, we might consider how he set out to distill the “big data” of knowledge passed on from his predecessors–indeed, the vast learning of the information-overloaded classical world–into pieces that could be taken in, retained, and used in smaller parts. For these reasons, medieval people often turned to the Etymologies for quick facts or the starting points of learning, just as many of us turn to Wikipedia.

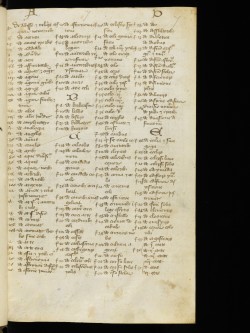

Medieval means of wrangling big data may be seen beyond Isidore’s production of his Etymologies, as part of the later transmission and use of this text. One example appears in Cologny, Bodmer 92 (pictured left, folio V7), a copy of the Etymologies produced in the early thirteenth century. On folios V7-V11, a user of the book from the later thirteenth or early fourteenth century has added a series of index tables meant to facilitate looking up and finding specific subjects in Isidore’s encyclopedia. Subject terms are alphabetized and keyed to specific references (e.g. “f.33.A. biblioteca” and “f.2.0.A. celestis”), which may be found by following the apparatus of the text throughout the codex. The index and textual references, then, work much like hyperlinks, allowing users of the Etymologies to find information about specific topics, rather than reading the whole book from cover to cover. In fact, as an abundance of evidence from medieval manuscripts shows, readers were likely just as used to jumping around books as we are with engaging in non-linear reading. This indexical feature in Bodmer 92 is one framework that users created for navigating the platform of knowledge in front of them. It is, in other words, a means of information management. This example demonstrates how later medieval users valued, revalued, adapted, and worked with Isidore’s Etymologies for their own needs. It also represents one way in which Isidore’s work–and medieval manuscripts generally–presaged certain later practices in the ages of print and digital media.

Once we start looking for such structural and organization frameworks in medieval media, even basic examples may be understood as part of the desires for book producers and users to come to terms with big data like the vast amount of topics covered in Isidore’s encyclopedia. Old media reveal how medieval platforms of knowledge were further manipulated for key content management. Bodmer 92 contains another example of such a technique in its basic rubrication. On folios 2r-v (pictured below), the scribe has provided a compact but decorated list labeled “Capitulum,” with the titles of the numbered sections appearing again as rubrications for chapter headings in the following pages.

For instance, the contents lists “III. De gramatica.” and the section headed with this title is found on the other side of the leave, on folio 2v (pictured above). What makes this system all the more striking as assistive is the use of different colors of ink: while the main text is generally written out in dark ink, the list of contents on folios 2r-v is signaled by the use of red and blue inks, and the headings for each section throughout the manuscript are rubricated in red. The start of each new section is also marked by a decorated initial, making the division more pronounced for browsable use. Additionally, the tops of pages are marked with alternating numerals to indicate the book (recto, in blue) or section (verso, in red) of the content in relation to the whole of the Etymologies. Although these various paratextual features are common in medieval manuscripts, the creator(s) of Bodmer 92 harnessed them to facilitate user-friendliness, to build readerly success into the book itself in the face of the big data of this voluminous encyclopedia.

I end this post with the start of a set of verses attributed to Isidore known as Versus in bibliotheca, which offers an exhortation to continual education as he saw fit for a world filled with innumerable knowledge. The following verses, in fact, seem as fitting in a world with the internet as they were some 1380 years ago, when even the information contained in books was more vast than a single person could master in a lifetime.

Versus in bibliotheca

These bookcases of ours hold a great many books.

Behold and read, you who so desire, if you wish.

Here lay your sluggishness aside, put off your fastidiousness of mind.

Believe me, brother, you will return thence a more learned man.

But perhaps you say, “Why do I need this now?

For I would think no study still remains for me:

I have unrolled histories and hurried through all the law.”

Truly, if you say this, then you yourself still know nothing.(Translation from The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Barney, et al., 16.)

Fascinating! I didn’t know this man existed until just now. Thanks Brandon!